Animating the Amiga: The Untold Story of Aegis Animator

Published 12 October 2025

Introduction: When the Amiga Brought Pixels to Life

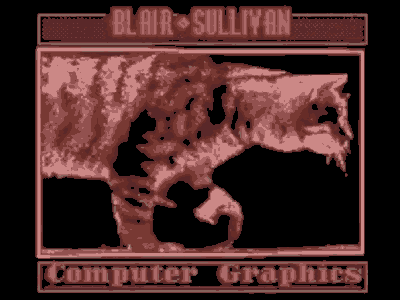

On the screen of a beige Commodore Amiga, a small cat takes a confident stroll across a blank grey floor. The animation lasts only a few seconds. Yet ElGato.anim—a looping demo from the late 1980s—captures everything magical about the Amiga: colour, motion, and personality on a home computer that felt alive. To anyone who saw it, that walking cat was proof that computers could do more than calculate—they could create.

During the mid-1980s, the idea of moving graphics was still exotic. Most home computers displayed static screens or simple sprite movements. The Amiga, introduced in 1985, changed that overnight with its custom chipsets—the Agnus, Denise, and Paula—that delivered multitasking, 4096 colours, stereo sound, and smooth animation. It was a dream for artists, designers, and bedroom experimenters alike.

Among the first software developers to harness these capabilities was Aegis Development, a California-based company that understood that creativity and accessibility could go hand in hand. Their flagship product, Aegis Animator, turned the Amiga into a personal animation studio. For many early users, this was the moment digital art stopped being theoretical and started moving.

Aegis Animator – Professional Tools for a New Generation

Released in 1987, Aegis Animator was marketed as the fastest way to animate on the Amiga.

The company's now-iconic advertisement in Amazing Computing magazine (November 1987, page 35) boasted the tagline: 0 to 60 in 3 seconds

. To a generation of Amiga owners, that speed wasn't about frames per second—it was about creative momentum. Load the program, sketch a figure, and within moments it was walking, bouncing, or exploding with colour.

Animator featured a clean interface with a set of tools that anticipated professional packages: frame-by-frame drawing, onion-skin overlays to track motion, and colour cycling for dynamic effects. Most importantly, it used delta compression, storing only the pixel changes between frames. That trick made playback astonishingly smooth even on a 1-megabyte Amiga 1000 or 500. The Amiga's blitter chip took care of the rest, delivering fluid motion that PC owners could only dream about.

Under the hood, Aegis Animator exported animations in the .ANIM format—a clever, chunk-based structure that became a standard across the Amiga ecosystem. Users could render their creations and play them back using a lightweight viewer called ShowAnim, which shipped on many Fred Fish disks and public domain collections. For budding artists, this meant they could create once and share everywhere.

While the later Deluxe Paint Animation and Scala Multimedia tools would dominate professional workflows, Animator had the virtue of being first. It arrived at a time when the Amiga's identity was still forming, and Aegis helped define what desktop animation

meant. For hobbyists and early multimedia enthusiasts, Aegis Animator was their window into a moving world.

ElGato.anim – The Walking Cat That Walked Into History

Every technology has its mascot. For the Amiga animation community, it might just be ElGato.anim. This charming short appeared on Fred Fish Disk 125, one of hundreds of public–domain collections distributed throughout the late 1980s and early 1990s. Each Fred Fish disk was a curated snapshot of creativity: shareware, demos, utilities, and small wonders like this one.

ElGato (Spanish for the cat

) is a simple but elegant looping sequence of a cartoon feline strolling from left to right. No background, no sound—just precise, believable movement. It's not the product of a large studio, yet it demonstrates the delta frame principle beautifully. Each frame stores only the parts that change—the legs, the tail, the bounce of the stride—resulting in an animation that looks effortless but is technically sophisticated.

Although the exact creator is unconfirmed, it likely originated as a demonstration file for Aegis Animator or ShowAnim, intended to showcase how compact and smooth the ANIM format could be. For users exploring their new Amiga disks, discovering ElGato.anim was a delight. It ran fluidly, looked professional, and felt alive in a way that few computers could match.

What made this small file so memorable was its accessibility. Anyone could copy it, show it to friends, or use it as a base for their own experiments. In user group meetings across the world, the cat walked across hundreds of CRT screens, a tiny symbol of the Amiga's creative promise. Even today, Amiga enthusiasts recall the walking cat as one of the first animations they ever saw that truly looked like film.

Software Preservation Efforts – Keeping the Pixels Alive

Decades later, many of those floppy disks have faded. Magnetic media deteriorates; proprietary formats vanish as operating systems evolve. Without deliberate preservation, the history of Aegis Animator and countless other creative tools could have disappeared into the digital dark ages. Fortunately, the Amiga community never stopped caring.

In the 2010s, software historians and developers began systematically archiving original disks and manuals. One major initiative, the Aegis Animator Software Preservation Project, hosts disk images, documentation, and restored binaries. It serves as both a technical resource and a cultural record of how early animation software was built. Much of the source code has been lost, however, the historical concext is still alive.

Preserving software is not just about saving code—it's about preserving context. Volunteers document version numbers, release notes, and even magazine reviews so future readers can understand how each tool fit into its era. The Amiga community's commitment to open distribution and public archives echoes the original spirit of the Fred Fish collections themselves.

On my own site, in Living in the Digital Dark Ages, I described the challenge of rescuing vintage software before bit–rot claims it permanently. A single unreadable floppy may represent the only surviving copy of a pioneering program. When those bits vanish, so does the creativity they enabled. Projects like the Animator preservation effort remind us that cultural heritage increasingly lives on fragile magnetic surfaces.

Preservationists also work to ensure legal clarity. Many Aegis titles, including Animator, are classified as abandonware, meaning the rights remain uncertain but the commercial value is nil. Archiving such works under fair-use and educational exemptions allows researchers and fans to study them responsibly. Where possible, original authors have granted permission for redistribution, further strengthening the archive's legitimacy.

Without these grassroots efforts, we would lose not only the software but also the mindset of an era. The Amiga community's collective volunteerism—uploading disk images, documenting source trees, and scanning box art—keeps alive a digital lineage that corporate archives rarely consider worth saving.

Legacy – The Spirit of the Amiga Lives On

When people remember the Commodore Amiga, they often recall its music trackers, paint programs, and the endless creativity of the demo scene. Aegis Animator deserves a place in that memory. It proved that motion graphics could be personal. Artists didn't need a film studio—they needed imagination, a mouse, and an Amiga.

The technology it introduced—delta compression, onion–skinning, and hardware–accelerated blitting–laid groundwork for tools that followed: Deluxe Paint Animation, Disney Animation Studio, Scala, and even LightWave 3D. The workflows pioneered by Aegis still echo in today's timeline-based video editors and keyframe systems.

Meanwhile, the modest ElGato.anim continues to charm collectors. It appears in emulator showcases, YouTube compilations, and retro festivals as a perfect emblem of early digital artistry. Unlike corporate mascots, this cat wasn’t designed for marketing&mdsah;it was born of curiosity, coded with care, and shared freely. Its persistence across decades highlights how communal creativity outlasts commercial lifecycles.

The legacy of Aegis Animator also reminds us that preservation is a participatory act. Each user who uploads a disk image, tags metadata, or scans a manual contributes another thread to the digital tapestry. The tools may have aged, but the philosophy endures: software belongs to those who keep it alive.

As we approach the fortieth anniversary of the Amiga, its animations still move with a vitality that modern hardware can't replicate. They carry the imperfections of CRT phosphor, the sync flicker of 15kHz video, and the optimism of a generation that believed personal computing could also be personal art.

Three seconds of animation, thirty years of memory—that's the enduring magic of the Amiga.

Further Reading & Resources

- Aegis Animator Software Preservation Project, GitHub

- Amazing Computing Magazine, November 1987 Advertisement

- Fred Fish Disk 125 – ElGato.anim Demo, philreichert.org

- Living in the Digital Dark Ages (philreichert.org)