Bally Astrocade Muncher

Updated 21 October 2025

Discovering the Astrocade

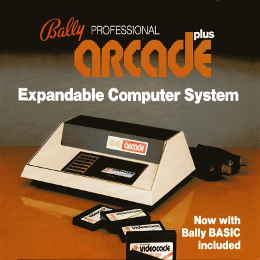

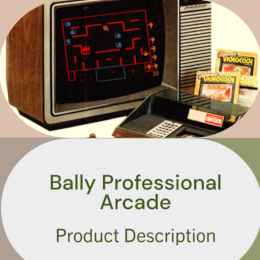

Before the Nintendo and Atari empires defined the rules of living-room gaming, Bally’s Astrocade attempted something bold: it invited its users to be creators as well as players. Released in 1977, the system wore many hats—it was a game console, a programmable computer, and a portal into a hobbyist culture that blurred the line between engineer and gamer. In a way, the Astrocade was years ahead of its time. While competitors fought over cartridges, Bally encouraged owners to write BASIC programs and share their creations through newsletters and floppy exchanges. To those who grew up soldering kits or typing code from magazines, it felt like belonging to a secret guild.

The Astrocade’s sleek wood-panel finish and futuristic controllers hinted at quality, but its fate was undermined by inconsistent marketing and limited production. Yet, for those who owned one, the console represented something more personal—a canvas for imagination. Its graphic chipset produced surprisingly colourful results, and the sound hardware could be coaxed into producing rich, expressive tones. Long before modern indie developers, Astrocade programmers were already experimenting with what could be achieved on limited hardware.

When Pac-Man fever hit

The release of Pac-Man in 1980 swept through the gaming world like a bright yellow fever dream. For arcades, it was a gold rush; for home systems, a call to arms. Everyone wanted a piece of the maze-chasing action. The Astrocade’s audience—already accustomed to tinkering and cloning popular titles—took it as a challenge. If Atari could do Pac-Man, why not Bally? Out of this grassroots energy emerged Muncher, a game that attempted to bring that same pellet-munching adrenaline to Bally’s hardware.

Muncher was not an official conversion. It was born from the work of independent programmers such as Ron Picardi, enthusiasts who reverse-engineered arcade magic in their spare time. What makes Muncher fascinating today is not just its resemblance to Pac-Man, but how it reinterprets the original through the lens of a different architecture. The Astrocade’s colour palette, limited sprites, and memory constraints shaped the game into something recognisably familiar yet strangely alien—a Pac-Man that had evolved in an alternate timeline.

Gameplay through a retrogamer’s eyes

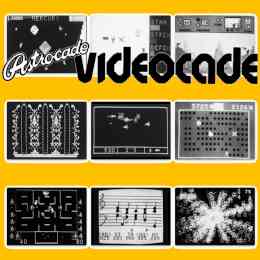

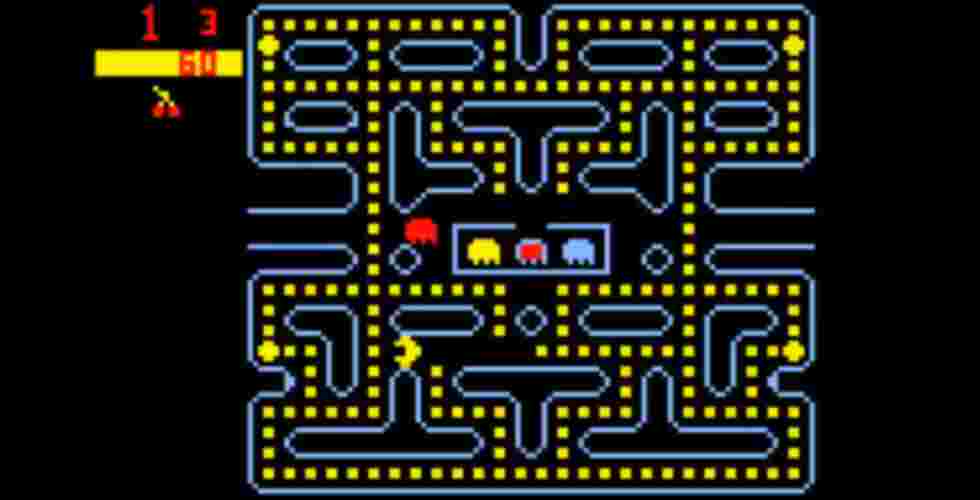

Booting up Muncher on original Astrocade hardware is an experience that immediately transports you back to that awkward but charming transitional era of gaming. The maze fills the screen with thick, gl01owing lines. The player’s “muncher” glides rather than darts, and the ghosts—each rendered in muted hues—move with a kind of erratic enthusiasm. There’s no background music, just the steady blip of movement and the occasional triumphant chirp when a power pellet takes effect. You can sense the hardware straining, yet the overall feel is hypnotic.

As a retrogamer, one learns to appreciate these quirks not as flaws but as signatures. Every flicker, every colour clash tells a story about the programmer’s choices. The limited video memory forced clever trade-offs: the maze’s layout had to be simplified, the collision detection tweaked for speed, and the ghosts’ artificial intelligence compressed into a few dozen bytes of code. These constraints give Muncher its texture. Play long enough, and you start to notice how the game communicates mood through rhythm rather than polish—it’s not a copy of Pac-Man; it’s a reinterpretation through the language of the Astrocade.

Compared to the arcade version’s endless loops, Muncher offers a more concise experience with around a dozen levels. That brevity, however, makes each stage feel deliberate. When you clear a maze, you don’t rush to the next; you take a breath, feeling the machine cool beneath your fingers. The ghosts speed up faster than you expect, the power pellets fade sooner, and that tension—the knowledge that the system itself is at its limits—adds to the thrill.

Privacy Statement: Video is powered by YouTube.

The myth of the Muncher advertisement

One of the enduring mysteries surrounding Muncher is a magazine advertisement that periodically circulates in collector circles. The image depicts a gorgeously rendered maze and character art far beyond the Astrocade’s capabilities. To modern eyes, it looks like a legitimate print advert, yet no one has definitively traced its origin. Was it fan art mistaken for an official campaign? A mock-up created for trade shows? The truth remains elusive, and that uncertainty has only fuelled its legend.

When you compare the ad’s gleaming visuals to the humble in-game graphics, the disconnect is almost poetic. It reminds us how imagination filled in the gaps between what we saw on-screen and what we felt in our heads. In the early ’80s, box art wasn’t just marketing—it was an invitation to dream. Muncher’s “too-good-to-be-true” advertisement captures that era perfectly: equal parts aspiration and illusion.

Legacy and reflection

For most gamers today, the Astrocade barely registers on the map. It sold modestly, was quickly overshadowed, and faded from store shelves by the mid-’80s. Yet, when viewed through the lens of retro history, it represents a fascinating branch of gaming evolution—one where creativity thrived within limitation. Muncher, in that sense, is more than a Pac-Man clone; it’s a time capsule of experimentation.

Looking back, what makes the Astrocade era so compelling isn’t the polish but the passion. You can almost imagine the programmers at their workbenches, coaxing miracles from kilobytes of memory, unaware that their efforts would still be discussed decades later by hobbyists, collectors, and historians. As a retrogamer, revisiting Muncher isn’t about chasing high scores—it’s about reconnecting with that spirit of discovery that defined the early home-computer frontier.